One of our friends from the Far Horizons Co-op successfully completed a Kickstarter for an RPG with the most amazing art you’ve ever seen. We spoke to Federico Sohns about their new RPG: Zephyr: An Anarchist Game of Fleeting Identities, chatting to them about its themes, character creation and gameplay, and its world, to get an idea of what people can expect from this unique game. We also managed to get them for a quick phone call, and now we’re even more excited about the game than before.

What is your ‘elevator pitch’ for this game?

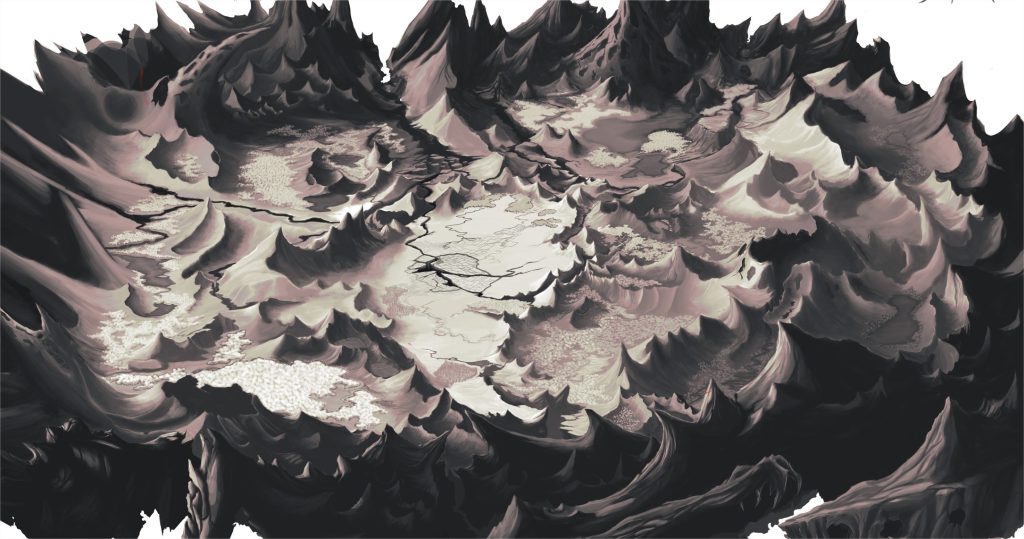

Zephyr: An Anarchist Game of Fleeting Identities is a roleplaying game set in the wandering, sentient continent of Ophoi. This entity travels on a relentless march across an endless salt flat, its four lungs bursting with sentimental energy – the alien emotions of the Zephyr, which comes in Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black. Like most substances, the emotions of the Zephyr coalesce into mountains made of rage, rivers of sorrow, fields grown out of the essence of guilt – everything that is, in its whole colourful gamut, including complex lifeforms. From these emotions and their fusion, the Windfolk are born. You are one of them, setting out from a far flung community in mountainous embrace, to travel this eerie continent in order to fulfil sacred obligations. These obligations are crafted by the players, becoming the main drivers for the narrative as well as the knots that tie your characters to the peoples they meet across the land.

How did you pick those 4 colours – cyan, magenta, yellow, and black?

I thought of colours that could create almost any other colour, so I took the CMYK colour space used by printers, because I thought it was a nice way to “rhyme” with the colorspace of printed books, and it allowed me to not get locked out when illustrating.

That’s a subtle bit of design there. Does each colour represent a specific emotion that you combine when playing Windfolk?

Each colour is an unknown emotion of Ophoi – which is unknowable to us or the Windfolk since it’d be like asking the Earth about what kind of feelings it understands to feel. But their tripartite combination creates the feelings that we and the Windfolk know. For example, CMY is Love, MMY is Rage, and so on and so forth.

Like an alchemy of alien feelings turning into feelings known.

Feelings are obviously very important in this world. Colours also represent bonds between Windfolk and the world, and shape the identity of individual Windfolk. That combination feels very deliberate and thought-out – identify, feeling, and bonds.

Yup, in a way everything we do everyday, and what makes us, is tied to things we feel strongly about. This is regardless of the fact we feel good or bad about said things – only things that we don’t consider within our sphere of existence can be something we don’t feel strongly or at all about.

It’s mostly also to counter a sort of scientificist, patriarchal view of the world in which feeling is relegated to a sort of throw-away category where the “subjective” and even the “supersititious” lies.

It also feels very distinct from the normal way of approaching character creation in RPGs. On the one hand, there’s the utilitarian version of picking from lists of classes, fantasy races, and equipment, like you’d find in a D&D clone; or the genre-aware approach of Powered by the Apocalypse where you pick from a list of archetypes and decide what kind of flavour you want to give it. In Zephyr, it seems that you’ve put a lot of thought into how identity is shaped.

Yep, particularly there’s a lot of weight put into how stories shape who we are. These traits that get picked stem directly from interpretations and take on well-known Windfolk stories.

You talk about that on the KS page – that you create characters by reading a Windfolk story in comic form, and then decide how your character responds. Specifically, was that part of why you decided to approach identity in this way – to distinguish Zephyr from what people have seen? Or are there also political reasons behind that decision?

There are political reasons behind every decision. It’s precisely to point at the importance of stories and their role in making people. We are constantly talking about this stuff, and waging war over the way we address, interpret, and contend with stories. Only today we are having a debate about the need to reject that Harry Potter video game. It’s a constant throughout history.

Indeed! Which stories we tell, whose stories we choose to participate in, which cultural narratives we engage with and propagate. These all have repercussions outside of entertainment. Real world consequences. I think RuneQuest does something similar in terms of character creation, but there players need to decide what their parents and grandparents did during important historical events. But yours is also explicitly an anarchist game. How important was it for you to include an anarchist viewpoint in your game design?

Since I’m an anarchist, the “viewpoint” thing is sort of impossible to alienate. I think the question is more about the anarchist themes – mainly about ways in which social institutions and communities form outside of (and often in opposition to) monopolies of the legitimate use of force. I made Zephyr during my whole journey into anarchism, and together with all of my reads tied to anarchist anthropology (or, the anthropology of anti-state modes of life), the game is pretty much an evocation of these feelings as I traversed them.

You just mentioned your journey into anarchism. And we’ve spoken before about your research into historical societies that rejected a state mode of life. Which texts or historical precedents did you find especially useful or insightful?

Plenty! The one that started it all, and that remains at the crux of the thing, is Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years – from which several of the main thematic topics of Zephyr come from. After that, big chunks of the writings on the world and their communities can be derived from James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State as well as Against the Grain. If I can quote more, then Wengrow and Graeber’s Dawn of Everything, Silvia Cusicanqui’s A Chi’Xi World is Possible, Pierre Clastre’s Society Against the State, Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse, Gehrda Lerner’s The Creation of Patriarchy, among many others.

Excellent, thanks! We love reading lists. Which themes specifically stood out for you, and which ones did you want to include in Zephyr?

We’ve briefly discussed Feelings and Identity, and the second axis is Debt and Obligation. In this case, the difference is marked in how debt is a form of obligation that is quantifiable, and because it is quantifiable, it is impersonal and exchangeable. In game, these two exist as the foundation of colliding worldviews – the obligations of the Windfolk, whom you play as, and the debts of the Salt States, the game’s main antagonists.

I love that the “big bad” in this game is basically a society of capitalist wage-slavers. You’ve explained that debt and obligation are explicitly part of the anarchist themes in the game. How are the bonds that Windfolk create with each other and the world of Zephyr different from debt and obligations?

Windfolk are conscious that Obligations are something that primarily serves to create relationships with one another, with material gains or any such things being secondary. Like, a date at the movies is an Obligation – but you wouldn’t say the main goal of the date is to watch a movie, rather, to get to know more about your date. People dating are conscious of that and it’d be obvious to say why that is not exchangeable. (I cannot say “sorry, I cannot go, you can go to see the movie with this random dude here instead.)

The trick is, Debt is also primarily a way to create relationships, its just that these relationships are of domination, and so its quantification and the idea that debt is made “primarily for the pure notion of profit-seeking” obscure the truth of the society they are reproducing.

In game, Obligations are the main driver of your stories. You start by creating an Obligation, defining how far you’ll travel for it, what it involves, what’s at stake, if the Obligation is tying you to a single windfolk, a group, or the entire community, etc.

And depending on that, there’s a measure of reciprocity (which I called Oi Points) that you can use to learn Technologies for your Windfolk. The more complex the Obligation you create, the more Oi Points you get to spend – since the community needs you better prepared to face the odds.

So the players are determining the details and goals of the journey and fleshing out some of their capabilities at the same time.

How do obligation and bonds fit in with emotion/feelings and identity – in the game, at least?

What’s funny about that question is that there’s literally a space in the character sheet that is used to connect Bonds (feelings) with Obligations. Basically, as you set out in your adventure to fulfil Obligations, you can spend tokens in the right combinations to start creating Bonds. These bonds have a feeling, an intensity rating (1 to 3) and a concept they are bound to – for example, Love (2) for Cooking.

So you go about fleshing out these Bonds, and when you finally fulfil an Obligation, you can create a Pattern – which is a particular drawing of woven lines – that weaves Bonds together and grants a particular power, the intensity of which comes from the intensity of the Bonds you have accumulated

Okay, so these philosophical, political themes are supported mechanically in the game. Why am I not surprised! How do these patterns affect the game?

They tend to be powers that more often than not interact with your scarf (an essential piece of Windfolk attire).

There’s plenty to choose from, some passive, some active. For example, one could be evoked to make the scarf cover a chunk of your face, and the Pattern works as “gills” that allow you to breathe underwater.

The cool thing is that each Pattern usually has several levels, but that do different things, and if you weave them in the right place to the right Bonds, you may be able to trigger different effects depending on the feeling you’re evoking. It’s a bit complex, but it has a lot of room to play with.

You said earlier that players determine the details and goals of the journey, and define their own capabilities simultaneously. I love this especially. I love RPGs that give you agency as a player, to decide what kind of campaign you’re committing yourself to. And that seems to be reinforced by what you’re saying about Patterns.

Yup! It also slightly changes the focus of the role of the storyteller – they are more free to focus on fleshing out the world, and they can shift into introducing unexpected turns to the narrative, rather than trying to make things go this or that way.

Okay, this sounds more and more like my kind of game. The use of coloured tokens to reflect emotions is another unique element of this game. They affect individual Windfolk and the world itself, correct?

Yep, tokens can be either on your character sheet a part of your Constitution (essentially, your body), or on the Regional Map as part of the Zephyr in your immediacies. There’s a continuum between the two as you hunt and gather and harvest Zephyr, and later on spend it to get you through all the challenges the world poses.

It’s almost as if your character’s emotions affect the world around you.

That’s kinda how the whole “world made of feelings” thing is expressed through mechanics, right?

Indeed. So that was also deliberate, correct? What kind of bonds do you foresee the world creating with the Windfolk?

Yep! It’s an interesting thing, bonds the world creates with Windfolk. A relationship of Obligation most often involves reciprocity – which is why the Windfolk do mind the personhood of trees, rocks, mountains, clouds, etc.

There is one of the initial Myths, The Judgment of Apha, that involves a river (River Apha) the Salt States used to flood and raid Windfolk lands. In that story, there is a trial in which the river is found guilty of cooperating with state incursions – and is duly “beheaded” with a dam.

So yeah, environmental stewardship is a thing.

In the same way windfolk care for the environment around them, the environment is meant to reciprocate.

That’s amazing. I love the world building already! Again, that doesn’t seem like something many RPGs are too concerned about – how your characters’ actions affect the environment around them. That was also a political choice, I imagine?

Yep, as everything. In the way of feelings, they are the same thing – the characters are just another state of personhood of the Zephyr, in the same way a river can be a mountain later in life, etc.

I like the way the whole world – environment, Windfolk, emotions – are presented as an integrated whole, all interconnected and affecting one another.

What should people expect from a game of Zephyr, either in a single session or over the course of a campaign? I’m seeing an opportunity for epic journeys, short trips to nearby clans or areas to find resources, dangerous expeditions to meet an obligation. Is that roughly the scope you have in mind?

Generally, a mix of survival play (so, making sure to have food and shelter), coupled with advancing their Obligations, and always mindful of the plan as they journey on – since the map is something that’s present at all times at the table. And always the chance for new Obligations to pop in the road.

Did you design the map yourself or did you outsource that? Did you get any other artists involved like you did for Nibiru?

Nope, I illustrated and did everything myself, all hundred-and-something illustrations.

Yowzer! For anyone who’s played Nibiru and its expansion, Xanadu before – how different is this game? Will they recognise the game designer, do you think? The gameplay and the setting are very different from your previous work. Which elements of Nibiru do you think carried across?

I think one aspect that has a strong parallel is the idea that there’s a resource you can use to succeed at a check, that also fleshes out your character in some way.

Flashbacks in Nibiru see their simile in Evokes in Zephyr (so, you spend tokens to establish bonds instead of memory points to establish memories).

Both games also seem very interested in exploration, and in giving players a lot of power over the world. Do you agree?

Yup, though Zephyr is more fleshed out mechanically – Nibiru is still what I’d consider a rules-light game.

Do you expect the same players to enjoy both games? Will Nibiru players find enough here to make it worth their while?

I think if you connect with the theme focused design, and the “novelty” aspect of my work, you’ll feel right at home. It’s certainly different.

You can pre-order Zephyr: An Anarchist Game of Fleeting Identities over at BackerKit.